Antarctica Part 5: Let's seal this deal

Back on the National Geographic Explorer, the staff organized a “what does this iceberg look like” contest. Rules were simple: take a photo of an iceberg you think looks like something, and submit it to the staff with a creative title of your choosing. The contest allowed for two categories; one permitting photo manipulation with words or simple drawings. The second had to be a standalone shot. The submissions were presented in a slide show and voted on by the guests. I entered the first category. Here’s my submission “The Loch Ness Monster.”

Will anonymously entered the second category with his photo “Uranus.”

Doing my best impression of a tabular iceberg.

It’s morning of our final day in Antarctica, and we are en route to Deception Island.

Deception Island is an active volcano, one of two in Antarctica. The center of this island is actually the volcano’s flooded caldera, which was created after a violent eruption some 10,000 years ago. In this super cool aerial view, the whole thing is a volcanic crater, as are the smaller circles you see, which were created from subsequent less violent eruptions.

Photo credit: modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2023

The only entrance into this gigantic crater is through the absolutely stunning Neptune’s Bellows.

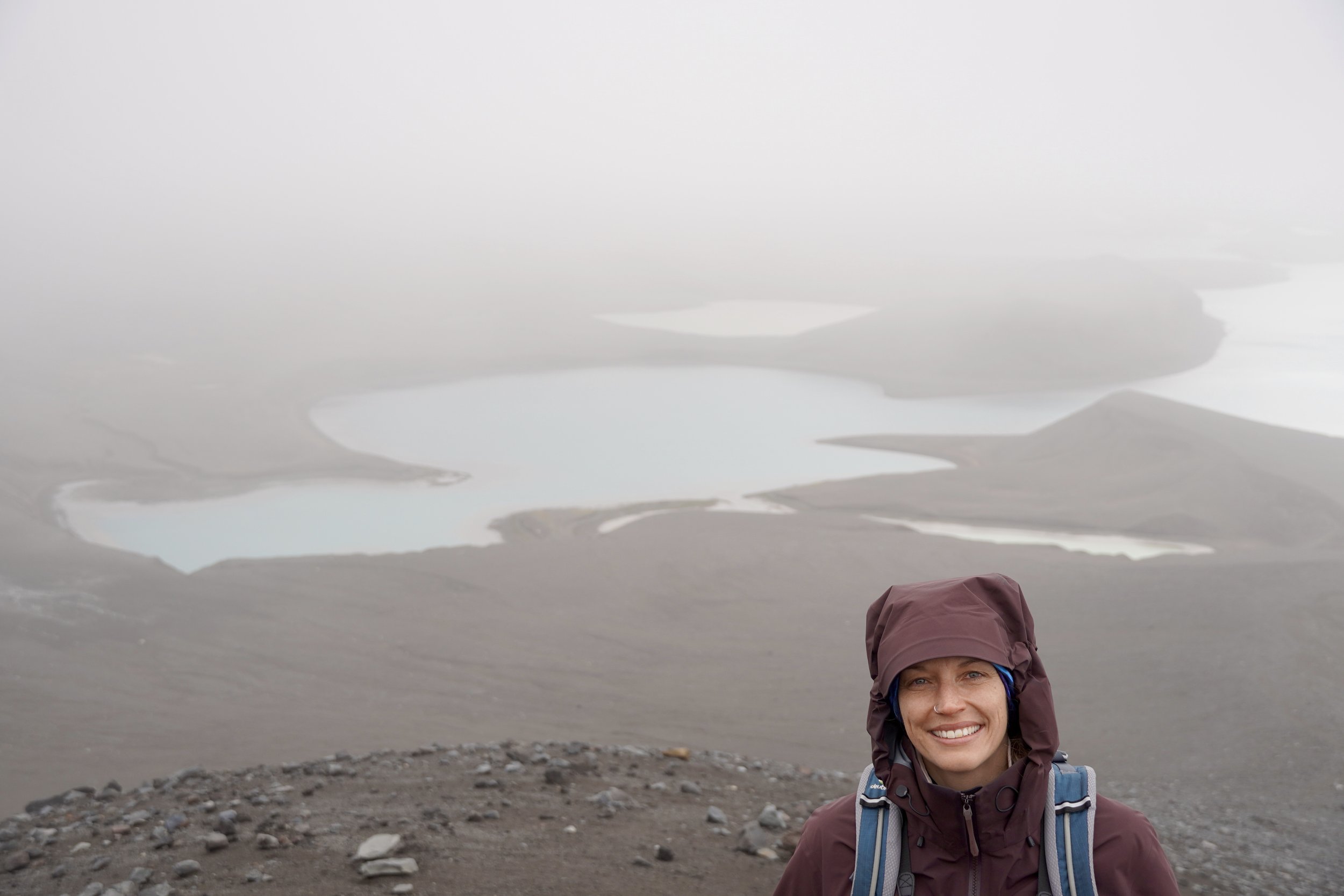

We landed at Telefon Bay and hiked up one of the many volcanic craters for some spectacular views and another round of spot the Canadians.

Penguin skull.

Leaving Deception Island.

That afternoon we headed to Livingstone Island with one final chance to explore Antarctica’s shores. Chinstrap penguins, gentoo penguins and elephant seals all nest on the island, while giant petrels, Wilson’s Storm-Petrels, and kelp gulls crowd the steep cliffs. Livingstone Island is so densely packed with wildlife, IAATO often deems it unsafe to bring people ashore, so it’s closed for landings most of the season. We were fortunate to have it open about a week before we arrived.

It was a loooong wait to board the zodiac for this final excursion. I napped and read while Will picked on the guitar. When our group was finally called we grabbed our things and headed down to the mudroom for disembarkment. Honestly, you would think the routine of it would be second nature by now… yeah, not so. We got half way down and Will noticed he forgot his lifejacket, so back up to our room. We got half way down again and we both forgot our scan passes (they won’t let you off the ship without scanning out so they can track the movement of people). Back to our room to get the scan passes. Back down to the mudroom. We donned our rubber boots and joined the queue to board the zodiacs, but we failed the biosecurity screen, so over to the poor sap delegated as penguin poop picker to get our boots cleaned. Back in line. By this point I was prepared to hurl myself over the edge of the ship and swim to shore. We were so disorganized we ended up being the last two people to leave the ship, so it was just us and our zodiac driver on our shuttle to shore, which was actually kind of nice. As we waited for the zodiac ahead of us to unload their moderately coordinated and only sometimes listening guests, the most fortunate thing happened. Right beside us, a leopard seal caught a penguin.

Leopard seals don’t eat penguins whole. It’s actually quite a gruesome ritual, thrashing the penguin around violently to first drown it, then skin it, eating only the meat and leaving the skin and innards for the hovering sea birds. This whole process took 16 minutes, but I have condensed some of the footage to a more attention-span friendly experience. Please excuse the commentary, we were pretty excited.

There was a frenzy of gulls and petrels hovering above the kill site as the gore of the poor penguin was flung about. The whole thing was painfully mesmerizing.

These crazy little birds are Wilson’s Storm-Petrels, locally referred to as “Jesus birds.” The get their nickname from the unique way they scuttle across the water. These tiny but mighty fowl undergo a surprisingly long-distance transequatorial migration. They can be seen as far north as the St. Lawrence River, and manage to make the long journey down to Antarctica, braving the winds of the Drake Passage alongside the largest birds on the planet.

Migration pattern of Wilson’s Storm-Petrel.

Just like a whale’s fluke, you can ID a leopard seal by the spotted pattern on its face and neck.

Leopard seals are massive creatures, up to three meters long. Later, we learned that leopard seals have been known to attack zodiacs, biting holes in their floatation bladders. Mathew, our driver, was keeping a close watch on her behaviour, but thankfully kept it to himself that her threatening advances could mean we were swimming to shore in leopard seal infested waters.

A leopard seal’s diet is 90% krill, but when the opportunity presents itself they will eat penguins and crabeater seals (a little more on these guys next, we did spot some). The conditions this day must have been perfect for penguin hunting as this graphic encounter happened three more times at this landing site, giving several zodiacs front row seats to the culling.

The inaptly named crabeater seals don’t actually eat crabs, they eat krill. They are the most numerous seals in Antarctica, with some speculation that they may be the most numerous large mammal in the world behind humans. Under the right circumstances, they are preyed upon by killer whales and leopard seals. This guy has a significant wound likely from one such encounter, but has managed to find a safe landing at least for the time being. Now back to the story.

Once the escapade was over we touched land for our last visit with the penguins.

Giant petrel nest.

Next, we were shuttled over to Walker Bay for a stroll on the beach where we encountered a pod of elephant seals. This belching, farting, stinky, moaning mass of moulting hair is not surprisingly a herd of males. Elephant seals go through a catastrophic moult, losing their skin and hair at the same time, which compromises their insulating outer layer rendering them unable to swim in the cold Antarctica waters. The moulting process can take 2-3 months. Because they are unable to enter the water to feed, they will lose 40% of their body weight. Non-breeding males will often spend their moulting months in groups, which is what these guys are doing.

Dominant breeding males, commonly referred to as “beach masters,” possess a harem of females that can number up to one hundred. Harems are so large, only 10% of male elephant seals reproduce and they can sire up to 125 offspring per mating season. Nursing mothers are beachbound for seven weeks after their pups are born. During this time the beach master must also stay ashore to protect his harem or he may lose his females. Jousting between male elephant seals is quite violent, lasts for hours and can end up being fatal.

Livingstone Island was the most northerly stop on our Antarctica expedition making it the most hospitable for plant life. Antarctica has over 350 species of mosses and lichen, but only two types of grasses, one being tree grass and the other is more of a tiny flowering shrub.

We also found deposits of copper and coal.

And some 35 million year old fossils, including this one of petrified wood.

This piece of petrified wood is evidence that 2.58 million years ago, before the most recent ice age, Antarctica was once forested. Here’s something I didn’t know: technically we are still in that ice age, the Quaternary Ice Age, but we are in an interglacial or warming period within that ice age. The peak of the last glacial or ‘cooling’ period was 20,000 years ago, and only four to seven degrees colder.

And just like that, our time was up.

We were shuttled back to the ship one final time for the bittersweet ending. As if to say goodbye, our evening recap was interrupted by a large clan of killer whales, swimming alongside the ship.

Over the next two days we were engrossed in the rough seas of the Drake Passage, riding the winds alongside the Albatross. It was a perfect time to reflect on the curiously foreign wilderness we had just encountered. We traveled thousands of kilometres to visit an ecosystem uniquely free from permanent human inhabitants, populated instead by life curiously adapted for the exceptionally unforgiving climate, and I was immeasurably grateful to have experienced it.

As we were piloted back through the Beagle Channel to the shores of Ushuaia, a pod of dolphins joined us for some bowriding shenanigans.

For a long while we watched them play carelessly below us before they split, a final whimsical goodbye from a capricious continent.

Thank you Antarctica for everything you shared. We may never come back, but we thoroughly enjoyed the journey.

The caves pictures above are some of the oldest human settlements in south-western Europe. They date back to the Neolithic Period, approximately eight thousand years ago. These cave sites, and their remnant artifacts have shed valuable inside on life during the prehistoric period in Spain. The caves are built into limestone cliffs, creating a natural shelter for humans and livestock. However, the arid climate, sparse rainfall, and persistent erosion cumulated into an inhospitable agricultural climate, and the economic consequences forced the settlers to move on decades ago. All that remain are the crumbling shells of what once was someone’s home. We saw them everywhere.